Attack on Pearl Harbor: A Brother's Story

By Richard E. Barry

(aka Rick Barry)

NB: Below is an excerpt from an family journal

currently in draft.

The Storm: December 7, 1941, Pearl

Harbor

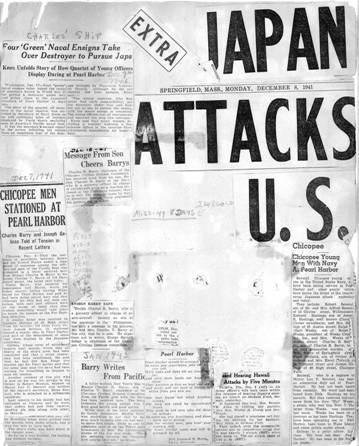

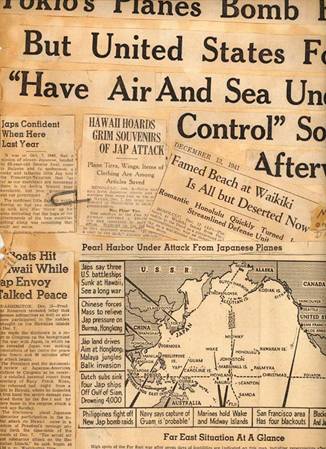

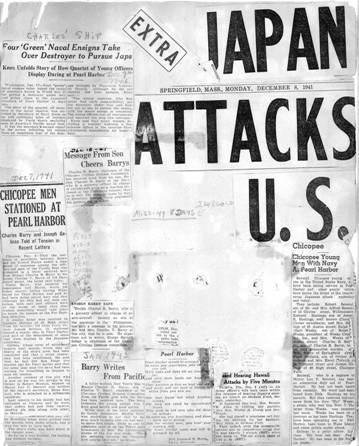

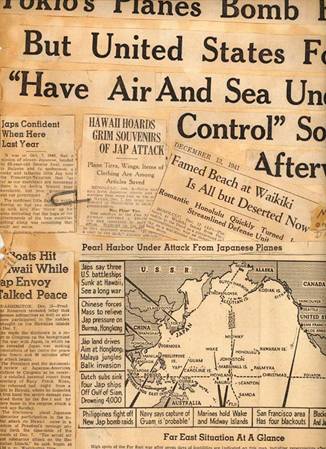

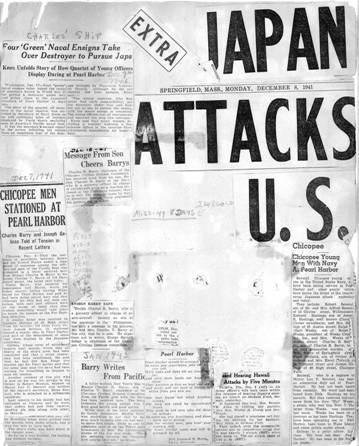

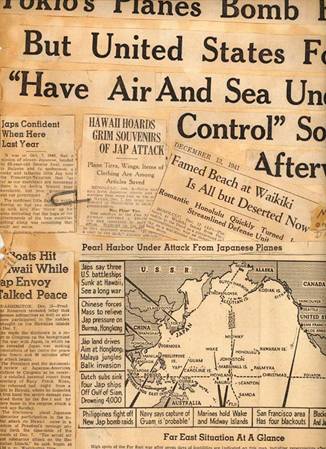

Front page, Springfield Union, Springfield, Massachusetts,

December 8, 1941

On December 7, 1941,

I was eight years old, the youngest of four brothers, living in Chicopee,

Massachusetts, just home from church. My oldest brother, Charles Bernard Barry,

or "Chuck" as we called him, who typically signed his letters home

as "

CBB", was a (recently 21 yr-old) Ensign Gunnery Officer on his first ship (DD-387),

the first of two ships commissioned as USS Blue. The 387 was torpedoed eight

months later during patrol off Guadalcanal near the Solomon Islands

as part of the Battle of the Eastern Solomons in the early hours of August 22,1942

scuttled the next day following unsuccessful attempts to save her or tow her

into port at Tulagi. By this time, Charles had already completed his tour on the

Blue and was serving on

another ship.

Like many, many other members of the

crews on ships that were anchored in the Harbor on that historic weekend, Chuck was on weekend

liberty. He was staying in room 205 at the Moana Hotel on Waikiki

beach in Oahu, Territory of Hawaii (T.H.) where he was

making ready for a tennis match with his skipper who was at the same hotel when the

Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor (about 25 miles away from

Waikiki) at 7:55 a.m.,

Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941. He

told me that he remembered hearing some distant sounds that he thought might be

"those crazy Navy

pilots" showing off on a Sunday morning with their practice bombing runs.

He took special big-brother pleasure during the Vietnam War period when I was a

naval aviator, in pulling my chain on this reflection.

In the day, shipboard officers were allowed to wear only blue or white uniforms

with black shoes. Aviators were permitted to wear those too but also had their

own winter green and summer khaki uniforms with brown shoes. The two groups

became known as "black shores" and "brown shoes. By the time I

was serving in the Navy, the khaki uniform with brown shoe privileges were

extended to all officers and thus the black-shoe and brown-shoe vernaculars lost

their meaning but, nevertheless, remained in common usage among the two

groups.

He called his commanding

officer, LCDR H. N. Williams, who was also on liberty and at the Moana, for a

planned 8 a.m. tennis date, only to discover from the skipper's wife that general

quarters had just been sounded and her husband had just left to return back to

Pearl. This was no drill!

As my brother retold the story to me, he commandeered an

Army jeep and driver

waiting for an Army COL boss in front of the Moana in its semi-circular drive and directed

the driver to take

him to Pearl Harbor, which he did under protest. My

brother told me that the roads were nearly impassible with traffic jams and that they

had to drive part of the way downtown on the sidewalks. By the time he got to Pearl,

the Blue had already gone to sea with its skeleton duty weekend crew.

My recollection is that my parents received the terrible news

from the Red Cross a day or two after the attack, by phone or telegram,

indicating that Charles was missing in action. With radio silence in effect at

sea for much of that time, it wasn't until a week after the attack that the

Detroit and Blue both returned to Pearl Harbor along with other ships and

"out of location" sailors were repatriated with their home ships and

their MIA designations lifted. That is when we could gratefully say that

Charles was a "Pearl Harbor Survivor".

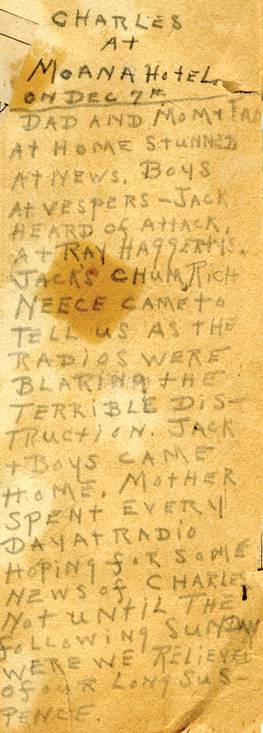

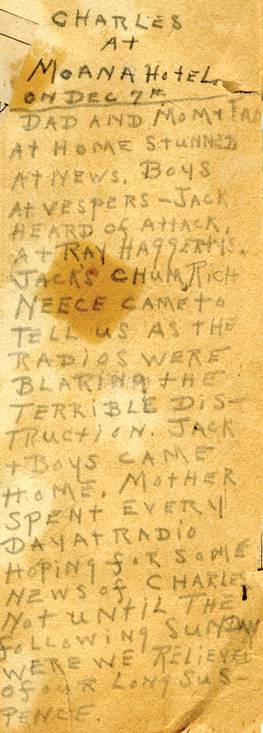

I remember walking home with another brother Neil from vespers. Below

are mom's recollections. I can't make out the word after "Dad and Mom

+…" perhaps "Family," but think that by the time Neil and I got

home the news of the attack had already just come through to the folks on the

radio.

USS

BLUE (DD-387), First

Ship Out of the Harbor?

Years

ago, at a convention before I had the idea of writing a family journal, I met

and briefly spoke to a retired military officer, I believe Army, who had

recently authored a

history book on the War. He had a stall there where he was selling his book. I

checked its index and found one reference to the Blue that indicated that it was

the first ship to leave Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 at 8:45 a.m. To my later and continuing regret, I didn't buy

the book Shamefully, I don't recall the author's name or the book title

and thus have been unable to confirm that assertion. That is to say, I've been unable to find any indications that

some other ship departed at an earlier time. Nor am I aware of any reference

listing times or order of ship departures from the Harbor on that day and have not yet been

able to search the deck logs of all ships in the harbor at that time. I know

that there

were command concerns that day that even if other larger classes such as

cruisers were physically able to do so, the risk was high that it might be torpedoed in the

kidney-shaped harbor and in the process cut off the escape route of the remaining

ships attempting to do so. However, after research at the

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park, MD, I have been able

to determine from the Blue's deck logs that it sailed out of

out of Pearl Harbor at 8:45

a.m. I'm also told that it would have taken about 45 minutes to crank up the boilers

of the Blue

and get enough steam up to get a ship of that size under way.

By the time my brother arrived on the shore of Pearl, again

like many others, he boarded a small boat shuttle taking men out to their ships.

Since the Blue had already departed the Harbor, he was first taken to the

battleship Arizona (BB-39) where he attempted to assist in the rescue of the

crippled battleship's entombed crew that subsequently became the grave of

its crew and now highly visited permanent monument. A more senior officer

present there asked him what his specialty was. Upon learning that he was a

gunnery officer, he was told that he was needed more immediately elsewhere and

was told to take the next incoming shuttle from the Arizona to the cruiser,

Detroit (CL-8), which he did, sometime before 10 a.m. The Detroit logs at NARA show that it was

ready to depart the Harbor about 10 a.m. but was ordered to

stand down from doing so, presumably for fear that it might be sunken in the

throat until it was later given the go-ahead to proceed after it appeared that the

attacks were over and fought valiantly against the Japanese bombers from inside

the Harbor until then. As with others serving elsewhere than their appointed

ships, Charles spent the next week in combat operations off Hawaii aboard the

Detroit.

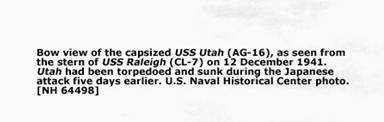

Now accessible from the U.S. Naval Historical Center, this

photo, was originally taken from a Japanese Navy plane gun camera at the

height of the attack, shows the Detroit, three other ships, that appears to be

firing its guns, as was reported in its own Action Report during the battle

prior to its departure from Pearl Harbor:

"Ships

are (from left to right):

"USS

Detroit (CL-8);

"USS

Raleigh (CL-7), listing to port after being hit by one torpedo;

"USS

Utah (AG-16), capsized after being hit by two torpedoes; and

"USS

Tangier (AV-8),

"Japanese

writing in the lower left states that the photograph's reproduction was

authorized by the Navy Ministry."

U.S.

Naval Historical Center.

Coming back to the Blue that fateful day: because most of

the ship's crew were ashore on weekend liberty, and according to ship deck logs

at NARA, the senior

officer standing the duty aboard the ship that weekend was Ensign N. F. Asher,

USNR. Being the senior of the four young reserve officers on board, and with a handful of enlisted

men, Asher took command and carried on heroically. This skeleton crew

represented itself remarkably as can be seen in the Action Report for December 7

that Asher wrote and dispatched on December 10.

In that Report, Asher claimed definite destruction of two Japanese aircraft and

one additional possibly destroyed. As well, he claimed one submarine definitely

sunk and possibly one other. He wrote:

| "0847 |

Underway – upon execution of signal to get underway – from Berth

X-7, Ensign N.F. ASHER, Commanding. Maintained fire on enemy planes with

main battery and machine guns while steaming out of harbor. Four planes

fired on with main battery were later seen to go down in smoke. It is

claimed that two of these planes were definitely shot down by this vessel.

one was seen to crash in field on Waipio Pena., and the second crashed

into crane on stern of U.S.S. Curtiss. Two planes that dove over

the ship were fired on by the 50 cal. machine guns. It is claimed that one

of these planes, seen to crash near Pan American Airways Landing at Pearl

City, was shot down by this vessel.

When abeam of Weaver Field landing, went to twenty five knots, and

maintained this speed while steaming out of the channel.

|

| "0910 |

Passed channel entrance buoys, and set course 120 true.

Proceeded to sector three to patrol station. Upon reaching station

commenced patrolling at speed 10 knots. |

| "0950 |

Good sound contact on submarine. Maneuvered to attack and dropped

four depth charges. Regained sound contact on same submarine. Dropped two

depth charges. investigated spot where the second attack was made, and

observed a large oil slick on the water, and air bubbles rising to the

surface, over a length of about 200 feet. it was first believed that the

submarine was surfacing, due to the appearance of the air bubbles, and all

guns were ordered to train out to starboard, so as to be ready to open

fire. It is felt that this submarine was definitely sunk. Approximate

location: 21°-11'-30" N and 157°-49'-45" W.

Obtained a third sound contack [sic] on a submarine that was

apparently heading for the U.S.S. St. Louis, which was at the time

steaming at high speeds on a course of approximately 150 true. Signal

"EMERG. UNIT 210" [these would represent bearings from the Blue

to the St. Louis and the reverse] was hoisted, and attack on submarine

made. Two depth charges were dropped. Upon a return to the spot where the

attack was made, a large oil slick was noticed on the surface of the

water. All contacks were made at about 1400 yards, and the submarine

tracked before the charges were dropped.

"It is claimed that one submarine, and possibly two were sunk."

|

I did not find documentation of any official confirmation of

these claims, and with the possible exception of USS St. Louis, I see no

evidence that the Blue was in the company of other units when these actions took

place that would provide a second verification of its claims. I'm aware that

many private efforts have been made in the years since the end of WWII to locate

sunken ships whose positions were reflected in official records, such as one or

more Japanese mini-subs found at the bottom of the sea off the coast of Hawaii;

but I have not researched such possibilities. It may be that the location of the

claimed "definitely" above might yield some evidence to make such a

verification possible. However, the Blue put clearly put in what must have been

one of the most successful days of any of the ships engaged in the battle. It was

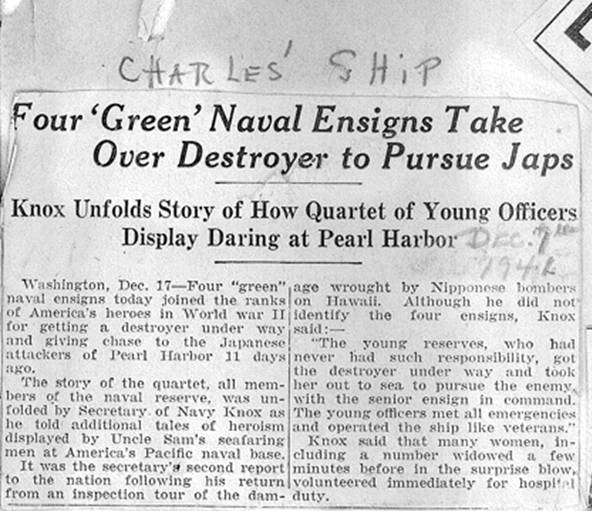

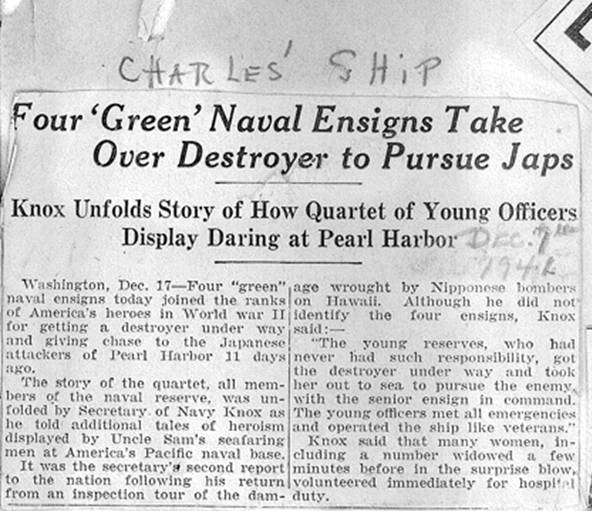

sufficiently so that it was the subject of the below December 17, 1941 Springfield

Union (Massachusetts) story, in which the young "green" duty crew

was singled out for high praise by the then-Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox:

A few years ago, I attempted to reach Asher, but learned that

he was long since deceased.

Mom's Scrap-Book Recollections

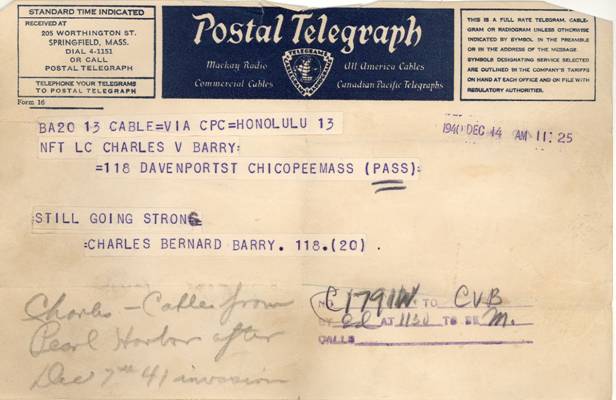

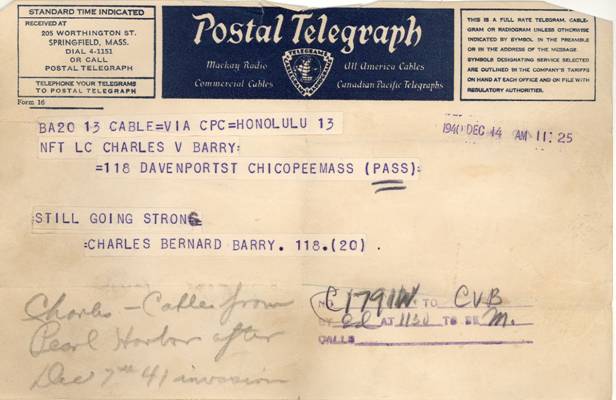

"STILL GOING

STRONG"

I recall another story that, upon first arriving at

Pearl from Waikiki, CBB just missed a motor launch

that was ferrying crews from shore to ships only to observe it blown out of the

water by a bomb from a Japanese aircraft. However, if it were true, I think it

would have wound up in one of the newspaper accounts that dad gave to the local

press. Not

being able to get to the BLUE, CBB wound up

on the USS DETROIT (CL-8 cruiser; only battleships and aircraft carriers were

larger than these warships) according to the newspaper account. Like many other

military people that day who had to get to any duty station they could, he was

listed as missing in action. Our family was extremely upset to learn this. It

was very tense for a whole week until we received a call from Western

Union with the below message from CBB. What wonderful news! What a

huge relief. The WU operator asked if we wanted a copy of the telegram.

"YES! Of course!" my father or mother who answered the call said.

Below is that telegram. My mother gave it to Charles after the War and he subsequently

passed it down to his only child, Susan Barry Nolan, for posterity, a cause that hopefully this journal

will extend to the whole family.

Scan

1010: "STILL GOING STRONG"

Scan

1010: "STILL GOING STRONG"

I did some research at NARA

to confirm that it was indeed the DETROIT

that CBB went to after finding the BLUE was

already at sea, and to discover how long he was on that ship before returning

to the BLUE. It turned out to be a somewhat

larger research task than I had originally thought it would be. First, I

obtained a copy of the key records in CBB's military

records by request to NARA's

military personnel records facility in St. Louis.

I thought I would find the DETROIT

or some other ship listed on Chzrles' list of duty

stations that would quickly answer both questions. But there was no such

reference. I was told by a naval archivist in the Research Room at NARA's

College Park, MD facility that this likely happened for many others in the same

situation that day and was probably due to: all the confusion during the

attack; the fact that there were no written orders to the DETROIT; and because

he was repatriated only days later to the BLUE.

In all likelihood, he was simply verbally ordered by a senior officer to make

his way to the DETROIT, which was

very likely still moored. So I continued the research by searching the daily

"Muster Roles" of both the BLUE

and the USS DETROIT with no luck. Then a Navy specialist archivist informed me

that in those days only the enlisted men were included in "Muster

Roles". He referred me to the full crew rosters that appeared at the

beginning of the ship's Deck Log records for each month. I first searched the BLUE

from December 7-14, with no luck. Since his above telegram was dated December

14, I assumed that he was back on the BLUE

by that date. I then searched the corresponding records for the DETROIT's.

The Deck Log of the DETROIT

for Sunday, 7 December 1941,

has a lengthy entry for the "8 to 12"

watch (military time for 8 a.m. to 12 noon),

which of course would have been the period during which the attack took place.

The attack would have taken place just as the watch was turning over; and the

first entry in the 8-12 report was: "Moored as before. 0755 Japanese

airplanes commenced dive bombing attack on Naval Air Station and ships in

port…Went to general quarters, set material condition "Z" and

commenced firing AA guns and machine guns. 0800 Torpedo planes made a

simultaneous attack on the battle ships, and DETROIT,

RALEIGH

and UTAH, moored at F-13,F-12 and

F-11 respectively." The end of that

watch entry stated: The following passengers reported aboard: from NEVADA…[listing

names]. From U.S.S. BLUE, C. B. BARRY,

USNR…" My best guess is that CBB

had a very hard and tense hour or so getting to the Harbor from the Moana and

thus probably boarded the DETROIT

around 9 a.m. or shortly thereafter,

but certainly before 10 a.m. when DETROIT cast off F-13 and got underway.

Judging from the prior entries on that watch, one might conclude at least two

things: 1) The Commanding Officer of the DETROIT

was no doubt happy to take on a Gunnery Officer, because the DETROIT,

in berth F-13, was among the first priority targets under siege. The adjacent RALEIGH

(DETROIT's sister ship (CL-8) in berth F-12) and the battleship UTAH

(in berth F-11) were both hit and the UTAH

capsized. And 2) It was clearly a very bad hair day for CBB and his shipmates.

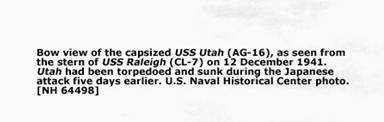

The story of the battleship UTAH

on that day according to the official Navy Website

reads:

"Shortly

before 0800, men topside noted three planes — taken for American planes on

maneuvers — heading in a northerly direction from the harbor entrance. They

made a low dive at the southern end of Ford Island, where the seaplane hangers were situated, and began dropping

bombs. The attack on the fleet at Pearl Harbor lasted a little under two hours, but for Utah, it was over in a few minutes. At 0801,

soon after sailors had begun raising the colors at the ship's fantail, the

erstwhile battleship took a torpedo hit forward, and immediately started to

list to port. As the ship began to roll ponderously over on her beam ends, 6-

by-12-inch timbers, placed on the decks to cushion them against the impact of

the bombs used during the ship's latest stint as a mobile target, began to

shift, hampering the efforts of the crew to abandon ship. Below, men headed

topside while they could. One, however, Chief Watertender

Peter Tomich, remained below,

making sure that the boilers were secured and that all men had gotten out of

the engineering spaces. Another man, Fireman John B. Vaessen, USNR,

remained at his post in the dynamo room, making sure that the ship had enough

power to keep her lights going as long as possible. Cmdr. Isquith

made an inspection to make sure men were out and nearly became trapped himself.

As the ship began to turn over, he found an escape hatch blocked. While he was

attempting to escape through a porthole, a table upon which he was standing,

impelled by the ever-increasing list of the ship, slipped out from beneath him.

Fortunately, a man outside grabbed Isquith's arm and

pulled him through at the last instant. At 0812, the mooring lines snapped, and

Utah rolled over on her beam ends; her survivors

struck out for shore, some taking shelter on the mooring quays since Japanese strafers were active.

Shortly

after most of the men had reached shore, Cmdr. Isquith,

and others, heard a knocking from within the overturned ship's hull. Although

Japanese planes were still strafing the area, Isquith

called for volunteers to return to the hull and investigate the tapping.

Obtaining a cutting torch from the nearby USS Raleigh (CL-7) — herself fighting for survival after taking

early torpedo hits — the men went to work.

As

a result of the persistence shown by Machinist S. A. Szymanski; Chief

Machinist's Mate Terrance MacSelwiney, USNR; and two

others whose names were unrecorded, 10 men clambered from a would-be tomb. The

last man out was Fireman Vaessen, who had made his

way to the bottom of the ship when she capsized, bearing a flashlight and

wrench….

The Detroit

would have been fighting off the same attacking aircraft that did in the UTAH

– looking at the above picture, one can't help but see a likeness to a giant

whale – and other nearby ships. Its log for the same watch indicates that DETROIT killed some aircraft and fended off several

others, as well as joining in on an attack of a Japanese submarine in the

Harbor. DETROIT got underway at

1010, but received orders from CinCPac not to leave Pearl

and "moored port side to in berth F-13", probably for fear that it

might be targeted to sink in the channel and close off escape by other ships.

At 1100 "No further attacks appeared imminent." DETROIT

was ordered underway at 1115 and passed through the channel at noon. It

had expended 422 rounds of 3" 50 caliber and 14,845 of .50 caliber machine

gun ammunition. No doubt Charles commanded if not manned some of those guns.

Scan

1010: "STILL GOING STRONG"

Scan

1010: "STILL GOING STRONG"