Evolving access solutions – repatriation of records

to indigenous communities

Helen

Onopko[i],

Records & Archive Services

Introduction

The western view of records tends to see the records

of aboriginal Australia as static, as something that can be used as legal

and historical proof. The indigenous people of Australia did not keep ‘archives’; they had no need to prove

their culture through documentation. Instead they rely on a complex system of

oral transmission and customary law. This clash of views leaves indigenous

people caught in a dilemma. Stuck between a traditional view of fluidity of

culture and heritage, an oral, living history; and the need to validate their

views by maintaining a static collection of documents and records of their

history and culture.

We

in the recordkeeping community need to review our understandings of the role of

archives, to evaluate how best our collections can be structured so that they

are not depositories of the past, but are also living places which are shaped

by the nature of the culture they document.

Issues

that I would like to cover include the following:

· Indigenous ways of understanding “archive” and the problematic

relationships between oral cultures and eurocentric notions of the archive, which

privilege written pasts

· Intellectual and cultural property rights in black law

· Examples where records are being repatriated to the

communities

What

we must consider in recognizing indigenous understandings of “archive” are:

§

location of

communities in relation to location of the records

§

financial

resources of researchers in getting to archives

§

the intimidating

alien environment of archives

§

research skills

of people looking for information

§

language barrier

- complex subject specific terms and formats utilised by professionals such as

anthropologists, governments, archaeologists

§

publications

& catalogues of records that are available, and the availability of these

indexes - if you don’t know what's there, how can you know what to ask for

§

the damaging

nature of many records - not wanting to make public things they did in the past

or opinions that were held in the past …… this fear can lad to 'conspiracy

theories', where in actual fact it is often just disorganisation and lack of

funds or time which make records inaccessible.

The late Fabian Hutchinson, said of central

Australian records:

"The

argument has been used that central Australia is one vast dustbowl where all archives would

automatically be 'at risk' as a 'reason' for perpetuating 'centralised' control

over records of research or policy value. This negative outlook denies the

actuality of local research requirements for records, and fails to consider

community values"

Intellectual

property and indigenous heritage

Celine

McInerney is an intellectual property lawyer for South Australian legal firm,

Norman Waterhouse. She has done

considerable work on Indigenous Heritage Rights in the context of Intellectual

Property under white Australian law and I have consulted her knowledge for this

paper.

The

concept of ‘Ownership’ is a key issue in clarifying the different ways that

indigenous and non-indigenous communities view the role of records and

archives. In changing our view of the role of archives, we need to give up the

concept of ownership, and of superiority in the correct use and interpretation

and our collections.

Indigenous

Heritage includes:

§

All items of

moveable cultural property including burial artefacts

§

Indigenous

ancestral remains

§

Indigenous human

genetic material (including DNA and tissues)

§

Documentation of

Indigenous peoples heritage in all forms of media (including scientific,

ethnographic research reports, papers and books, films, sound recordings).

§

Under Indigenous Law:

§

Cultural

heritage is collectively owned by the relevant clan, through individual

custodians of the stories, the dreams and so on;

§

Notions of

ownership, in the sense white people think of them, don’t apply;

§

The result of

this is that white laws don’t recognise many rights indigenous people believe are

important for the continuation of their culture.

Richard Robins pointed out in a 1996 discussion paper on the

changing role of Museums in Aboriginal Cultural Management :

Museums

need to recognise Aboriginal interests in their culture and that they have

primary rights over that cultural material.

…It may also require the museums to acknowledge that relationships, not

objects, have primacy.

Existing

archives legislation does not stipulate who can access a particular

institution’s records. This lack of enforced regulation gives no protection to

records which may contain personal and culturally sensitive information. In

addition to this, Museum legislation tends to focus on anthropological and

scientific issues, and not on the cultural and spiritual value to Indigenous

peoples of institutions’ collections. We are still in a situation where

Indigenous cultural material can be destroyed or willfully distorted with no

recourse. Cultural material can be misrepresented, and sacred and secret

materials can be accessed and used by anyone the current legal 'owners' of

these items see fit.

On

the one hand free accessibility to this heritage is needed so that Aboriginal

people can trace their genealogies, find their tribal identity, their ancestral

lands, and trace their relatives. On the other hand 'free' access can go

against traditional methods of control over the flow of cultural sacred

information. As recordkeeping professionals we can appreciate that here is a

special circumstance where context is as important as content.

In

July 1978, photographs by a powerful collector of aboriginal records were

printed in Stern Magazine showing sacred sites and secret rites of indigenous

groups. He was very upset when the

photographs were then sold to People Magazine.

Stern subsequently apologised. The whole controversy about whether the

photographs should or should not have been published caused a great deal of

moral anguish. He said that he had every

right to permit use of the photographs because the subjects in the photographs

had passed away.

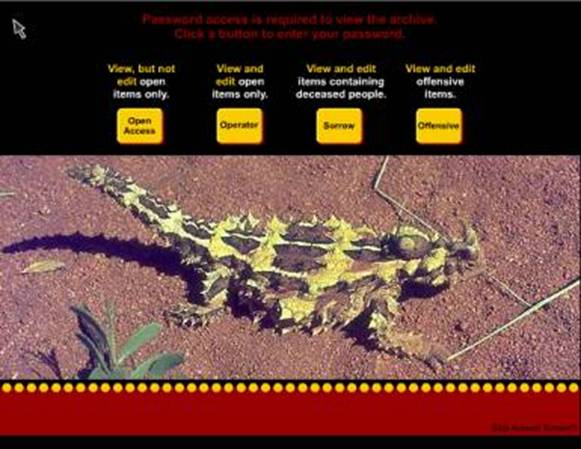

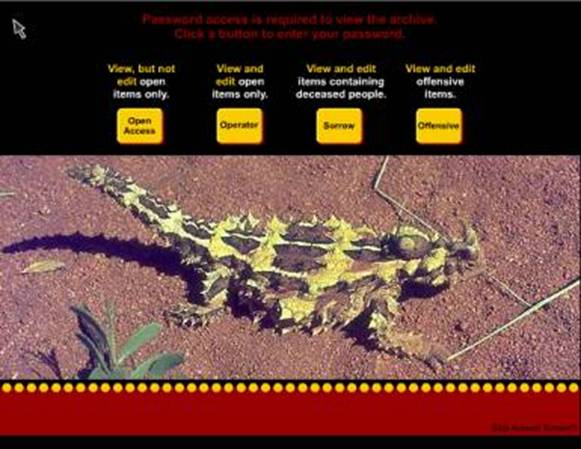

In

some Aboriginal communities, seeing the names and photographs of the deceased

may cause sadness and distress, particularly to relatives of those people.

It

is admittedly very difficult to write history without including such names. On

the Ara Irititja website, cautions are

provided to users, so that choices can be made prior to record access.

This

was placed at the beginning of the website and the warning has to be accepted

by all users to enter the site.

Example

of an initial access page (interface) within the Archive

(Images courtesy- John

Dallwitz, Ara Irititja Archive Project Manager)

The

closest we have come to providing indigenous Australia protection of their cultural heritage is the ATSI

Protocols for Libraries, archives and information services established in 1994

/ 1995.

Remember,

these collections may include sensitive material which must be respected and

treated specially. In order to respond

appropriately, organisations should make reference to the published protocols.

Protocol

4: Description and classification of

materials

What

must we do? We must

§

Develop, implement and use a national thesaurus for

describing documentation relating to Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples and issues.

§

Develop and use subject headings and guidelines for

archival description which are sensitive to Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples and which promote effective

retrieval.

Mick

Dodson in 1993 said:

We

have been referred to and catalogued as 'savages' or 'primitive' while Western

industrial peoples are referred to as advanced and complex.

Protocol

11: Copying and Repatriation of

Records to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities. Archives and libraries often hold original records

which were created by, or about, or with the input of particular Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander communities. Some records may have been taken from the

control of the community or created by theft or deception.

What

must we do? We must

§

Respond sympathetically and cooperatively to any

request from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

community for copies of records of specific relevance to the community for its

use and retention.

§

to the repatriation of original records to Aboriginal

and Islander communities when it can be established that the records have been

taken from the control of the community or created by theft or deception. ;

§

Seek permission to hold copies of repatriated records

but refrain from copying such records should permission be denied.

§

Assist Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander communities in planning, providing and

maintaining suitable keeping places for repatriated records

Keeping

places

Libraries,

archives, central filing places, museums and galleries are usually given

distinct and separate roles. One approach to the situation where a community

wants to reclaim its history, is for items from all of these places to be

brought together in one place of reference. In addition to this it is important

that such places are close to the communities whose people are the subjects of

the records. Issues of access can be made more difficult by the fact that

records are often housed in locations which are great distances from the communities.

In

Indigenous communities in Australia the term ‘keeping place’ has begun to be used to

refer to these multipurpose places.

‘Keeping places’ are:

§

libraries, in

that they house information which is a resource for the community

§

archives in that

they file, protect and maintain precious records,

§

museums and

galleries in that they hold items of archaeological and anthropological

interest and often have exhibits demonstrating the context from which these

items were created.

§

retail outlets

and businesses running cultural tours or art classes.

Current repatriation projects

Following the ATSI protocol, many communities and

archival institutions are cooperating to establish repatriation

arrangements. There will always be

resistance through interpretation. The

common statement we have encountered is …

We do not have any records created by

indigenous communities, only those about them, so there are no

issues of repatriation for us to consider.

§

So, what is

happening around Australia. A sample –

but certainly not an exhaustive list -

of repatriation projects follows:

§

Karratha Library

§

The Victorian Koorie Records Taskforce

§

Tibooburra Keeping Place, NSW

§

Djomi Museum (Bawinga Aboriginal

Corporation, Maningrida, NT)

§

Quirindi and District Historical Society, NSW

§

State Library - SA

§

NT Archives

§

Lutheran Archives - SA

§

Kimberly Communities

§

Ara Irititja Archival Project, South Australia

Karratha

Library

The

Library & Information Services Division, Western Australia contacted the Karratha Library to advise that

records on microfilm in their collection were being heavily accessed by

researchers from that area looking for family history information. They

suggested that the Karratha Library purchase a copy of the microfilm, making

the records immediately available to the community (along with a reader!)

The

Victorian Koorie Records Taskforce

The

Victorian Koorie Records Taskforce has released its report of the “Finding Your

Story Community Forums 2002”. The

purpose of the forums is to inform the community about what records are kept

and how they can be accessed. It is also

an opportunity for the community to raise any issues they may have about access

to their records.

Tibooburra Keeping Place, NSW

Opened

this year by the Local Aboriginal Land Council, the Tibooburra Keeping Place contains a collection of artefacts found in the

local area. The Australian Museum assisted in the creation of the keeping place, supplying support,

skills and knowledge. The impetus behind the creation of the keeping place was

the wish to preserve and protect those relics and artefacts unique to the

Tibooburra area.

Djomi Museum (Bawinga Aboriginal Corporation, Maningrida, NT)

The

Djomi Museum serves as a community keeping place. The museum’s collection

includes about 1000 photographs. In 1995 the Bawinga Aboriginal Corporation

was awarded a community heritage grant from the National Library of Australia

to digitise the photographic collection.

Quirindi

and District Historical Society, NSW

Quirindi

and District Historical Society has established a keeping place which includes

an archives, a newspaper microfilm collection, and artefacts from the local

indigenous community as well as the local non-indigenous community. The McLean

Phillips Collection contains aboriginal artefacts, artworks, photographs,

ceremonial items.

State

Library - SA

The

State Library in South

Australia is

taking a pro-active approach to making their records accessible to the

community. Repatriation of items is not considered to be of high importance as

the records at the library give reference to aboriginal communities, but

are not the actual records of those communities. Our Library adheres to

the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Protocols for Libraries, Archives and

Information Services. As such they are attempting to make their collection as

accessible as possible to Indigenous people.

NT Archives

Northern Territory Archives have a Protocol for Access to NT

Government Records by Aboriginal People Researching their Families and the

National Archives, Territory Office, has a similar Memorandum of

Understanding. These formal agreements

include commitments by the Government Archives to provide storage for

aboriginal community records and to repatriate copies of records to

communities.

Currently,

the NT Library & Information Service is sponsoring a strategy of creating

knowledge centres in Aboriginal communities.

Part of this strategy is to include in the knowledge centre a place for

keeping the records/archives/memories.

Lutheran

Archives- SA

The

South Australian Lutheran Archives gained a Government grant from the Cultural

Ministers Council to write a guide to the indigenous records in their archives.

The grant was made possible as part of the governments response to the

‘Bringing them Home’ report.

The

guide, published in 1999, is an index of names of people mentioned in the

archives. It acts as an initial place for people to search. Once records have

been found, people are permitted to photocopy the information, such as entries

in books. Unfortunately most people in the photographs which date back to the

1880’s are not identified.

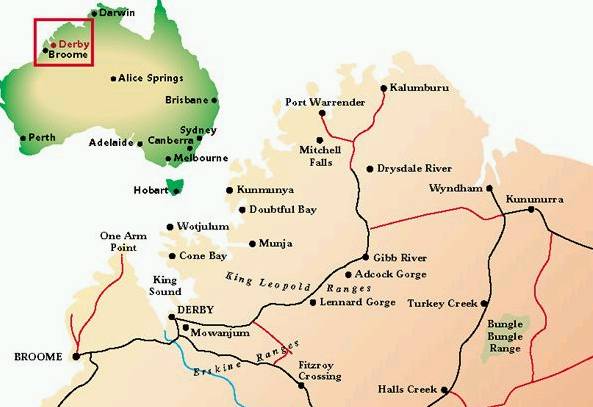

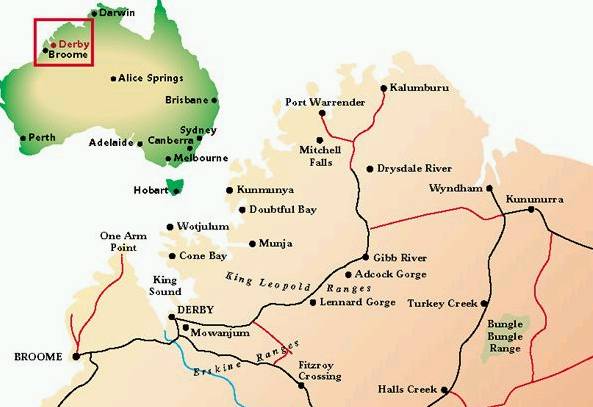

Kimberly

Communities

The

community in the Kimberly has begun their repatriation process, mostly of

material images, historical documents and paintings. Theirs is a very different

view of an archive. The land is an archive. They are very concerned about

heritage protection of objects on land that they have recently reoccupied.

[See slide presentation: slide #11]

The

community has also started organising and indexing for storage, and working out

presentation and some access issues. At the end of last year (2001) their

archivist Jenny Bolton began developing a classification system and with a

consultant, a database.

Currently

Jenny is waiting on approval to get a server which will link up the Land

Council’s five regional offices to the database. The Land Council is also

investing in the training of an indigenous library trainee, who will be able to

maintain the collection into the future.

Ara

Irititja Archival Project, South Australia

The

Ara Irititja Archival Project identifies, copies and electronically

records historical materials about Anangu

(Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara people). A private community project, the Ara

Irititja Archives were conceived by and are now managed by the Pitjantjatjara

Council. The SA Museum hosts the

project, supplying a place for the ‘hardcopies’ and ‘originals’ of the

materials to be safely housed. This

material was previously held in museums, libraries and private collections. John Dallwitz, Manager of the Project, explained that once people knew their

records would be safe and secure, they were happy to lend them.

The

software utilized by the project is culturally sensitive in that it regulates

access to private, sensitive and offensive materials. Added to this is the

capacity for Anangu to utilize a dynamic database such that when viewing

records they can add, expand, or correct data and historical details. Anangu

people who are in remote communities are encouraged to access the project

through mobile workstations equipped with computer, projector, printer and an

uninterruptible power supply.

[See slide

presentation: slide #12]

These

workstations are brought to remote communities and have also been installed in

several central locations such as Alice Springs and Adelaide. These stations run the archive as a self contained

unit. As such they don’t rely on telephone lines or an outside power source

(each unit has a 240v battery backup).

Since

its establishment in 1994, the archive has accumulated over 26,000 records. The

focus of the project on retrieving and securing records for the benefit of Anangu

and the broader Australian community means that the collection will continue to

grow.

[See slide

presentation: slide #13]

Granddaughter

and grandmother check existing archival records (Images

courtesy- John

Dallwitz, Ara Irititja Archive Project Manager)

Many

indigenous communities and individuals have contacted the Ara Irititja project

team regarding setting up their own such archives. However most are unable to

access the funds required.

[See slide presentation: slide #14]

Students print out photographic records on

the printer located inside the mobile workstation (Images

courtesy- John

Dallwitz, Ara Irititja Archive Project Manager)

One

success story is the Sisters of St John of God in Broome, who have purchased the projects software to begin a

project of digitising their collection of around 7000 photographs.

Conclusion

It

is a cruel twist of fate for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

that the records generated by the Government regime that tore their lives apart

are now in many cases the key to rebuilding their lives and identities.

Our

dilemmas:

Power

of destiny –v- unintended disclosure

Physical

access –v- intellectual access

White

interpretations –v- black knowledge

In

conclusion, there are differing views as to the merits of returning records to

indigenous communities. On the one hand people have argued that "an

informed aboriginal population will have a much greater feeling of power over

its own destiny". On the other hand, people have argued that in handing

over records there is a high possibility that the wrong people will be given

information. In such a situation, an existing oral tradition could be destroyed.

Handing

the records over may increase physical access, but what about intellectual

access. Indigenous communities will still be dependent on specialists

(often non-aboriginal) in the interpretation of these records. In the past, we have described the records

for our purposes, not theirs. This might undermine their roles as

history-tellers.

And

what about observations which researchers recorded. In most cases these

researchers were not aboriginal. They may have mixed with communities for up to

several decades, yet they are still outsiders. Their view is always going to be

based on this.

In

short, G K Chesterton summed it up well:

The culture of the conquered can be

injured and extinguished simply because it can be explained by the conqueror.